ALL I ASK IS A TALL SHIP & A STAR TO STEER HER BY

Arriving back at home after a three hour trip through traffic on the 401 in Toronto is always a relief, but double so if you’re getting home the first time after having a hospital visit. My niece and nephew were waiting for us and it was a relief to see them again. Alicia had left me a bunch of great food options, including a delicious quinoa salad.

The heart attack happened on a Sunday, the stents installed very early the next morning, and I was discharged from the hospital in Peterborough on the Wednesday afternoon. As I mentioned in No More Skittlebräu, there was a bit of boredom while in the hospital. I don’t blame anyone for that; hospitals are not supposed to be fun places, and it’s no one’s job to entertain patients. But the reality is that I am only capable of going without intellectual stimulation for a couple of days. Cottage fever was setting in, and I needed something of note to actually do. That’s when I decided to go back to work starting on that Friday.

Yeah, that does sound really unwise. And I’m not saying it wasn’t unwise; but, I did go back to work on my terms. I decided in advance that I would only work when I wasn’t tired, I wouldn’t do anything stressful, and I’d take a break or a nap whenever I felt like it. Clearing my schedule of everything that might induce stress was the next step, and I can’t thank my team at work enough for stepping up to help during my convalescence. Going back to work so quickly might seem foolish, but it turned out to be exactly what I needed. Using my brain in the way that work can stimulate really settled me down and put several things into perspective.

This is usually how I feel at work

Informing my team during our weekly Friday project meeting was easy as pie. The team I manage is, in a word, fantastic. They were concerned for my situation and made sure that I was in a good place, by both checking that I had everything I needed and doing whatever they could with their work to keep me as unencumbered as I wanted to be. Being towards the end of the summer, we were also in a bit of a lull. In my industry, we tend to have a slowdown over summer and Christmas; so it was good timing in some perverse way.

And let me tell you, a heart attack and a bunch of new meds can make an eepy guy. As a result, I was taking all of those naps I would promise myself not to avoid. I’m not sure if it was the fatigue from the heart attack, or the relief of not being dead, but the post-myocardial infarction naps were especially sweet. That and waking up from a long (8-10 hours) night’s sleep was the most refreshed I’ve ever felt. As my body repaired itself, it was doing many things simultaneously, but two were front of mind. First, all of the energy it was using to heal was making me tired, so the sleep (the necessity of it as my body became weary every day) felt especially earned. Second, because I was on a strict diet, and had virtually no appetite anyway, my body was “eating'“ its available energy resources.

I was losing weight, and fast. In the seven months since the heart attack, I’ve lost over forty pounds, dropping from just over 230 to just under 190. But most of that weight, probably nearly 35 pounds, happened in the first six weeks. The health pros certainly had a lot to say about that, but most of it was something along the lines of…

Okay…good that you lost the weight…but that’s way too fast.

Obviously, I was also concerned about losing weight that quickly. But it did make sense. Between my body needing as much energy from all sources as it could get, my appetite being almost nonexistent, and my caloric intake being significantly reduced, it was no wonder the pounds were evaporating. Part of that included the lovely experience of ketosis. Extremely fruity/sweet taste in the mouth, urinating as much as Secretariat (or maybe I should pick Northern Dancer as a result of Trump’s new tariffs), and general discomfort in my tumtum. For almost two months, I’d wake up five to six times a night, need to urinate like Frank Drebin, and spit out a metric ton of acetone-laced saliva. Despite all that, I was still experiencing some of the most restful sleep of my life.

The lack of appetite was extremely interesting, something I’d never experienced before. I wasn’t afraid to eat: some sort of fear that eating anything even remotely unhealthy could kill me. My stomach was unsettled, but I was able to keep food down for the most part. In the space of an entire week, I’d feel hunger pangs perhaps twice, and they were minor. I just didn’t feel hunger. I had virtually zero biological interest in food.

But when I did eat, it was, comparatively, an extremely boring experience. So, what did my pro-heart health / diabetes prevention diet look like in those early days?

BREAKFAST

Yogurt

Honeycrisp Apple

or

Cottage cheese on toast

Peach

LUNCH

Tuna wrap (very light amount of mayo) with lettuce and onion

or

Turkey sandwich with lettuce and onion on sourdough

Celery, carrots, broccoli

DINNER

Baked rainbow trout with onion and peppers

Salad with extremely light dressing

Raw veggies

or

Alicia’s quinoa salad with chicken breast

Not exactly the table d'hôte at The French Laundry, but it was keeping me alive. Since then, my menu has expanded, but there are so many items I just can’t eat anymore. And walking through the grocery store was a constant reminder of the new reality. More on this topic to follow in another post.

The medical team was expanding almost exponentially. Besides the two cardiologists in Peterborough, and my family doctor, I’d also been assigned a new cardiologist in Toronto who will follow me through the entirety of my care, and a cardiac surgeon who would be installing my new stents. There was also a new endocrinologist and a dietician to work me through the diabetes. I was immensely grateful for all their help, and have done what I can to follow their advice as closely as possible. In future, I’ll talk about yet another cardiologist, a psychiatrist, and a group of talented cardiac rehab kinesiologists.

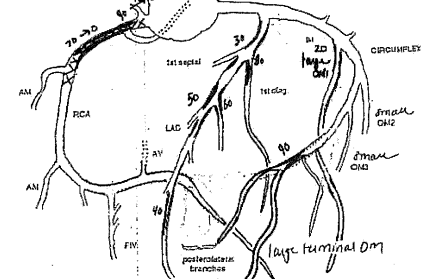

Given the results of the first cardiac catheterization, more stents were necessary. With Jenny in tow, as supportive as she always is, I was checked into Mississauga Hospital on August 20, 2024. Fortunately, the intent would be outpatient surgery. And it would also not require general anesthesia, which, at least at first, I thought was going to be fantastic. I was thinking back to the first surgery, and hoping that this one would be as intellectually stimulating. I was feeling a slight amount of anxiety going in, exacerbated by a very rare code blue in an adjacent cath lab, that resulted in a dozen or so doctors and nurses hurriedly flying past the pre-surgery waiting area.

The following section might be a bit too unpleasant for some readers. So, if you don’t like hearing about unpalatable medical procedures, skip the paragraphs in light text and the next two images entirely.

Let’s just say it was an exiSTENTial experience

After a bit of a wait in prep, I was popped onto a gurney and wheeled into the cath lab. The setup was nearly identical to what I saw at PRHC. However, this would be a more lengthy procedure, as several stents would need to go into the left anterior descending artery. At first, the experience was pretty similar to the first go-around. But it didn’t take long for it to start feeling very different and very uncomfortable. Out of necessity to complete the surgery, Dr. P needed to inflate incredibly small balloons in certain arteries to delivery medication and restrict blood flow. The result was a an almost indescribable, pervasive, crushing feeling like my life force was being sucked out of me.

And remember, this is for posterity, so be honest -- how do you feel?

This was, undoubtedly, the most unpleasant experience of my life. I’m in no way exaggerating this, but the heart attack was preferable. If stents are necessary in the future, it’ll be under general anesthesia. If that’s not allowed, whoever takes over this blog can cue up “guess i’ll die.jpg” in my absence. I never want to go through that again. But, let me be clear: I don’t blame the medical staff for this one bit. Jam a bunch of stuff into a dude’s heart and go figure that it makes for a distasteful encounter. They did amazing work to prolong my life, and I cannot thank them enough. It just sucked absolute ass. Additionally, I should point out that this is just my experience. I have no idea what that procedure is like for other patients, and, dear reader, I have no idea what it would be like for you. But I hope you never have need of it.

Due to some minor complications, the surgery ended up being longer than expected. I emerged from the cath lab and went into a kind of low grade shock; extreme cold, teeth chattering, back pain, general discomfort, nausea, and temporary insomnia. All of this, and the extended surgery, resulted in the hospital staff deciding to keep me overnight. I spent the next few hours trying to warm up and position myself in bed in such a way as to avoid the pain. When I wasn’t able to fall asleep, the nurses finally put me out of my misery with a much-needed sleeping pill.

The good news is that I woke up the next morning feeling wonderful. And I’m not just referring to a reprieve from the after-effects of the surgery. I actually felt even better than I had before the surgery, and perhaps even better than I had before the heart attack. Sure, the morphine was probably helping, but I guess if you improve blood flow through a heart you can count on a improved quality of life in general.

This improvement had me feeling extremely optimistic about my future. I hesitate to consider the heart attack to be a “wake up call,” but, in many ways, it certainly was. Not so much as an opportunity to repair the mistakes of the past, or do better, but to, at a very minimum, enjoy my life far more by respecting my life far more. This isn’t some epiphanic moment or religious awakening. It’s simple recognition that all I know is my own experience, and how it intersects with others, and so I have to focus on not losing all that I know.

WHAT’S NEXT? Your mileage might vary, but my healthcare experience was stellar: a big thank you to everyone who saved my life.