AWWW…NO HELICOPTER?

Dr. C had just informed me that I’d had a “STEMI,” but that I was stable. However, if there wasn’t further intervention, that would probably change pretty rapidly. Because the hospital in Haliburton wasn’t a full-service medical centre, I’d need to be moved somewhere that could perform a more thorough inspection of the ol’ ticker. The plan was to throw me into an ambulance or perhaps an Ornge helicopter and send me to Peterborough for further treatment. Despite my current state, I was pretty jazzed with the idea that I could get a ride in a whirly bird, so I was hoping that would be the option. In fact, even though I had kinda sorta almost died, I had been making several jokes as soon as they got me on the gurney

I’m not sure if it was a coping mechanism (which, knowing me, is entirely likely), or I subconsciously didn’t have much doubt that I was going to survive this, but it seemed natural to be a bit of a smart ass. I don’t remember the exact things I said, but much of it was probably about being an idiot, or feeling good enough to use my rolling IV tree as a dance partner. It wasn’t all shenanigans, as I did have a brief but important conversation with Jenny [more on that in a later post].

Beep boop blip blurp

I had no idea what a STEMI was before all this, much less what ST-elevation was. Have a look at the image above: on the left is a normal ST segment, and an elevated ST segment on the right. As you may recall from my previous post, the graph from the single-lead EKG on my Apple Watch wasn’t showing the elevation. But that could be for many reasons. First, it’s just a single-lead EKG, not nearly as accurate as the six- or twelve-lead EKG’s with which I was about to get very familiar. Secondly, it’s just an Apple Watch; a fine piece of hardware that can do a lot of cool things. But, if you’re expecting it to be a precise medical instrument, then I have some land to sell you in coastal Florida (it’s fair to mention that Apple makes it really clear that it can’t diagnose heart attacks). Last, but not least, it’s possible that I didn’t actually start having the STEMI until later in the evening, after the last EKG reading from the watch.

The big question was “what was causing the heart attack?” It was almost certainly a significant blockage. But how big, and how much damage had been done? The troponin blood test results were encouraging, but that could quickly be meaningless if I didn’t receive further treatment. The closest cardiac catheterization lab was in Peterborough, Ontario, about ninety minutes away by road. Sadly, the helicopter wasn’t to be, though I did get a good laugh when I shared my sadness at missing out on that potentially exciting (or maybe vomit inducing?) experience.

Awww…no helicopter?

Unfortunately, they don’t allow family in the ambulance, so Jenny had to follow along in the car. I was bundled off into the back of the “bus,” with C, the amazing nurse [fun side note: I found out later that she’s related to the people who run the local hardware store near the cottage!] and two fantastic EMT’s. On the trip, I was informed that ambulance drivers in these rural areas aren’t allowed to exceed 120kph. I’m pretty sure we must have been doing that speed pretty consistently for the whole trip, as we arrived at Peterborough Regional Health Centre lickety split. I spent most of the trip staring at the ceiling, checking out what stuff had been jammed into the shelving on both sides, and chatting with the nurse and one of the EMT’s. They were pretty cool about keeping me calm and administering whatever ancillary medications I might need. The trip went by fast, and I felt incredibly safe throughout.

PRHC

Arrival at PRHC was very smooth, and I was immediately brought into a sub-department of the intensive care unit. Jenny arrived shortly thereafter, and there began a litany of discussions on what my care should be. The professionals were pretty sure that the damage to my heart was minimal, but still significant enough to require, at minimum, exploratory cardiac catheterization. They were careful to point out that this might be more than just an exploration, and, depending on the inspection, they might need to do more (including the insertion of stents). The only question was whether or not it would happen that night, or could wait until the morning. Though Dr. S was off for the night, she decided to come in and do the surgery right away. I was wheeled down into the cath lab and the doctor and nurses explained everything that would happen. Fortunately, they were able to insert the catheter via my right wrist, and didn’t need to go in through my groin area.

The procedure was absolutely fascinating! I don’t recall exactly if I was offered to be under general anesthesia, but I think the preference was to keep me conscious. The room itself was exactly what you’d expect from a modern hospital. Sterile, bright, and full of some pretty impressive-looking technology. For those who don’t know, I work in technology myself. In fact, I’ve done work for hospitals, and always find those projects to be amongst the most fulfilling. In those few times working in hospitals, installing or consulting on audio visual equipment, I never thought about being in one of those rooms as a patient.

I was moved from the gurney to the operating table, covered in an array of lead clothing, and a IV line went into my left wrist. Through this line, they would inject me with a dye that would be used by the x-ray machine to see how blood was flowing through my heart, etc. To my left, about three feet away, was a 50” flatscreen display. The medical staff would use this to see the results of those x-rays, and, most of the time, I could see it, too. The x-ray machine was then wheeled in-place and positioned over me. It was on an articulating arm that could move about to get exactly the correct angle required.

Despite the lead suit (not at all like what Tony Stark must experience), I could still tell how cold it was in the room. It had to be that way, as the entire team had to wear protective clothing themselves. I could see how some people would consider the experience something that might trigger claustrophobia. Fortunately, I didn’t experience that at all. I felt comfortable, aware, and engaged throughout. When the x-ray machine wasn’t blocking my view of the display, I was able to see the catheter moving around, and the flow of the dye and blood.

The Ol’ Ticker

Check out this bad boy

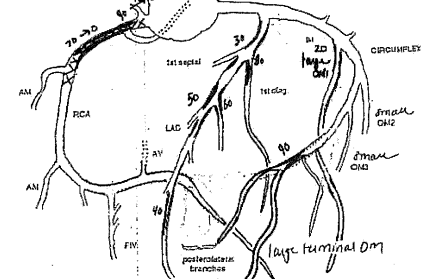

The portion in the top left corner of the image above shows the biggest problem area. This is the right coronary artery (RCA), which, as you can see from the notation, was 70% to 90% blocked at the culprit lesion. The standard procedure in this case is to insert a stent into the artery. There’s some debate over the etymology of the word “stent,” with competing theories indicating either an obsolete Middle English term for stretching; or the work of 19th century dentist, Charles Thomas Stent. Basically, this fairly modern medical device (first used in 1986) is a metallic or polymer tube that is “inserted into an anatomic vessel or duct to keep the passageway open,” etc. Via a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), Dr. S inserted a Boston Scientific Promus Synergy 3.5 x 38 drug eluting stent into my RCA [for the record, I don’t know if it was the “Megatron” variant, but fuck me, I really hope so]. All hail the amazing nerds at Boston Scientific for inventing this thing; and coming from one big nerd to other nerds, I promise that is a huge compliment.

As a quick aside, I want to point out that I felt absolutely no discomfort during the procedure. I was able to chat with the staff, as they spent a decent amount of time explaining what they were doing and the results. I’m not so completely out-of-touch with reality that I’d want to suffer a heart attack to experience the surgery, but, I have to say that the procedure itself was captivating and intellectually stimulating. Part of me wishes I’d gotten it recorded on my mobile phone, but I’m pretty sure they don’t allow that. In a later post, I’ll describe the second set of stents that were installed a few weeks later. That experience was pretty much the exact opposite of enjoyable.

I don’t remember how long the surgery took, but Jenny tells me that I was in there for about two hours. It concluded with the doctor explaining everything, describing the next steps for my care at PRHC, and that I’d need subsequent stenting sometime soon. I experienced a strong compulsion to thank the team for their amazing work, and I made it clear that I was grateful for their life-saving efforts. Suffice it to say, the quality of their work was exemplary and I consistently felt respected and safe.

Back in my room in the ICU, Jenny and I discussed how we’d reach out to friends and family to inform them of what happened. We decided to wait until the next day, and I settled in to get some sleep.

WHAT'S NEXT? Hospital recovery, lots of calls and text messages, and overwhelmingly warm and helpful support.